While one person is more sensitive to negative experiences, another focuses more on the positive. Within NSMD, PhD student Laurens Kemp investigates whether such different learning styles play a role in the development of mental disorders.

Suppose you regularly ask people on dates. Sometimes they accept, sometimes you are rejected. If you mainly focus on the negative experiences (the nay-sayers) and much less on the positive ones (the yes-sayers) and adjust your future behaviour accordingly (don't ask anyone else for the time being), we can speak of a 'negative learning asymmetry'. A positive learning asymmetry, on the other hand, is not necessarily positive, explains Laurens Kemp. "Because then you may be inclined to pay little attention to risks, which can get you into trouble. And if you focus mainly on negative information and learn less well from positive information, that might mean you're more susceptible to developing an anxiety disorder. That is also what I want to investigate: does learning asymmetry play a role in the network of symptoms that is a mental disorder, according to the network theory?" That, in a nutshell, is what Kemp is looking at in his four-year PhD research, in scientific terms: learning asymmetry as a transdiagnostic factor. He started in February 2021.

How did you spend the first year?

"I am adept at methodology, so I developed a task that I think best measures learning asymmetry. That was quite a challenge, because I'm a bit of a perfectionist. I don't think previous scientific attempts to measure this have been very successful. Because I can quickly see what the downsides of a task are, mine ended up being quite complex. We are now testing it with 150 test subjects and we have yet to see whether it will measure what we want to measure."

What was the hardest part of developing that task?

"To start with the problem: in conditioning, you look at how people respond to a stimulus that leads to an outcome. For example, you administer a small electroshock three times while showing a triangle and no shock once coupled with a square. How do people then react the next time they see a triangle, versus when they see a square? The problem with such experiments is that people do not react primarily like animals. They get all sorts of thoughts about the experiment, what the goal is, or about the researcher. I wanted to develop a task that would be influenced as little as possible by the thoughts of test subjects."

Why is that so important?

"Because those thoughts are not relevant to mapping their learning asymmetry. We purely want to know how people learn from positive or negative information, and that is a primary reaction to how they experience things. So I had to find a balance between an experiment that wasn't too simple to fathom, like many conditioning experiments, but also not too difficult."

Can you tell us something about the task that subjects are currently presented with?

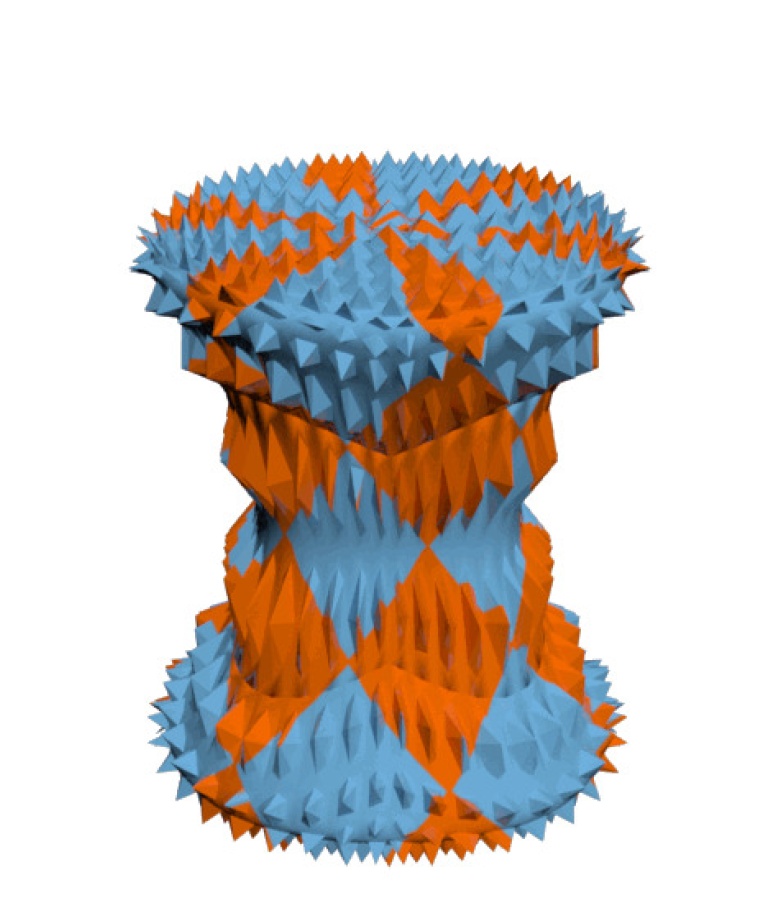

"In most studies, associations are formed with very simple stimuli and outcomes, such as triangles and squares. For the best quality research results, it helps to make the stimuli as complex as possible, but still unique and distinguishable from each other. A research group led by Professor Watson had already developed 3D figures once, but the script used to generate them was full of bugs, so I had to make them myself to a large extent. It was a lot of work, but the result is beautiful: a set of many different 3D objects, with patterns, colours, textures. We present these objects one after the other, linked to a positive or negative result. And after seeing 20 objects, test subjects are asked whether a certain object had a positive or negative association. The better they do, the more points they earn, the higher the financial reward. If someone especially remembers the negative associations well, that says something about their focus on negative stimuli rather than positive ones. We are now testing people with this to see if we can properly measure their learning asymmetry in this way."

And what is next?

"What my next three years will look like depends on the results of this and the next study, in which instead of winning or losing points, we administer nice or nasty tastes linked to the same 3D objects. We're also taking questionnaires about people's personalities, and with that we want to eventually try to say something about the relationship between these learning asymmetries and susceptibility to mental disorders."

You started your dissertation in times of corona, did that have an effect on your research?

"I think the threshold to participate in this research online is lower thanks to corona, but at the same time you have less control than if people came to the university. For example: even though I ask people to use a mouse for the task, we see that 60% of people use a touchpad or touchscreen. In other respects, too, it was not ideal to start in corona time, especially for making contacts. I am originally from Langedijk, north of Amsterdam, and moved from Amsterdam to Maastricht when I started. Yet it was easier for me than you might think, as I had already graduated from university five years earlier."

What did you do in the meantime?

"My last master's internship was not such a great success. I went to Sweden for it, but on both sides we had not prepared well enough and there was a character mismatch between me and my supervisor. I am grateful that we were able to complete it with a master's thesis, but it was not helpful for my network and that did not help when applying for jobs afterwards. I was also rather picky about what I applied for: I didn't feel like going into business. To fill the time, I had also signed up as an pet sitter and that developed into a full-time job. For four years, I cycled from one place to another to walk dogs. I didn't earn much but I could make ends meet and I must say: it makes you very happy. Until corona started and people started walking their own dogs. And, of course, it was not the job that suited my master's degree in Brain & Cognitive Science. So when I came across the vacancy for this PhD position, I wrote and was enthusiastic immediately. It felt like I had never stopped doing scientific research."

So no more dog walking for now?

"When I see people walking dogs in Maastricht, I do miss it a bit. But at the moment I prefer doing PhD research."